"Pink slime" might soon have a leaner presence in public schools than many might have initially anticipated.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture announced today that it will offer schools an option between two types of ground meat to purchase for student meals. The move is in response to requests from districts amid a weeks-long firestorm of public outcry against the ammonia-treated cow product.

The controversy was spurred by a report earlier this month by The Daily revealing that the USDA planned to purchase 7 million pounds of ground beef for schools that is mixed with "lean finely textured beef," or what has been nicknamed "pink slime." Two microbiologists, Carl Custer and Gerald Zernstein, said they warned the USDA against the "high risk" product years ago, but federal officials did not heed their advice.

The lean finely textured beef is a low-cost product rendered from the mostly fatty outside trim of cow carcasses or leftovers from other cuts. To salvage every bit of meat, the trimmings, combined with connective tissues and cartilage, are heated at a low temperature to remove about 95 percent of the fat. The resulting product is then compressed into blocks to be mixed into ground beef and treated with ammonium hydroxide (essentially ammonia and water) to kill pathogens like E. coli and salmonella that could have emerged during the rendering process.

Discovery of the USDA's purchase prompted Houston mother of two Bettina Siegel to start an online petition on Change.org asking Secretary of Agriculure Tom Vilsack to "please put an immediate end to the use of 'pink slime' in our children's school food." The petition had more than 225,000 signatures as of Thursday morning.

The USDA contracted to buy more than 111.5 million pounds of ground beef for the National School Lunch Program, with 7 million pounds of it coming from Beef Products: This South Dakota-based company produces lean finely textured beef. No more than 15 percent of Beef Products' ground beef mix for schools may be composed of lean finely textured beef, according to the USDA.

The announcement grants schools the option to purchase either 95 percent lean beef patties made with Beef Products' mixed product or fattier bulk ground beef without the controversial mix. The change will not affect schools until the fall as a result of existing contracts.

But districts may have always had that choice. Administered by the USDA, the National School Lunch Program's purchases account for 20 percent of the food used in U.S. schools. The rest is bought by schools or districts directly through USDA-approved private vendors. The distribution of USDA and private vendor products varies by school.

But districts may have always had that choice. Administered by the USDA, the National School Lunch Program's purchases account for 20 percent of the food used in U.S. schools. The rest is bought by schools or districts directly through USDA-approved private vendors. The distribution of USDA and private vendor products varies by school.

The Chicago Public Schools elect not to purchase ground beef from the USDA and instead buy ground beef from two USDA-approved private vendors, schools spokesman Frank Shufton told The Huffington Post. "It's not even a part of the picture," Shufton said.

The Chicago district is one among several that have issued statements assuring concerned parents that it does not use the ammonia-treated lean beef mix. When schools use that product, it shaves about $0.03 off the cost of ground beef, according to a 2009 New York Times report. But other school districts say they still can't afford not to purchase from the USDA.

Schools that participate in the National School Lunch Program receive cash subsidies for meals in compliance with USDA's nutritional standards.

'IS IT STILL SAFE?'

"I have people asking me, 'So is it still a safe product?'" Zernstein, the retired USDA microbiologist, told HuffPost. "And I say, 'Well, hopefully they add enough ammonia. Hopefully. Hopefully."

Questions about ground beef's safety have become more frequent after the 2009 New York Times report revealing that despite the added ammonia, tests of lean beef mix in schools across the country revealed dozens of instances of E. coli and salmonella pathogens. From 2005 to 2009, E. coli was found three times and salmonella 48 times; this includes two contaminated batches of 27,000 pounds of meat, according to the Times.

When treated properly, the "filler" is absolutely safe for consumption, Zernstein says; it could even be safer than the raw beef muscle it is added to. Problems arise only when the trimmings aren't sufficiently to eliminate the heightened rancidity levels and bacteria that emerge during processing -- and when testing is lax or regulations aren't strictly enforced.

Still, the USDA contends that the products it purchases adhere to safety guidelines. Ammonium hydroxide is also "generally recognized as safe" by the USDA and the Food Safety and Inspection Service.

"All USDA ground beef purchases must meet the highest standards for food safety," USDA spokesperson Aaron Lavalles said. "USDA has strengthened ground beef food safety standards in recent years and only allows products into commerce that we have confidence are safe."

'BEEF' ISN'T EXACTLY BEEF

Schools aren't the only ones affected. According to an ABC News investigation, lean finely textured beef is mixed into 70 percent of ground beef sold in supermarkets across the country -- but meat-packers and grocery stores aren't required by law to include "lean finely textured beef" on package labels because the USDA categorizes it as meat.

Beef Products and other industry players have sought to debunk "myths of 'pink slime,'" asserting that beef trimmings are 100 percent USDA-inspected beef and edible.

"Our lean beef is 100 percent beef," Beef Products spokesman Rich Jochum told HuffPost. "No other part of the animal or any other product is in our lean beef."

Even so, consumers and parents want to know just what they're consuming, says Siegel, the Lunch Tray blogger who started the Change.org petition.

People don't feel it's quite right to refer to both lean finely textured beef and ground beef as "beef," Siegel said. "It's about the overall issue of disclosure."

The controversial mix does have some useful qualities. Adding the product to otherwise very lean beef patties makes the texture of the cooked meat softer and more appealing. Its production could be termed a sustainable practice in that it salvages protein that may otherwise be wasted and it makes ground beef cheaper: Fresh 50 percent lean trimmings -- the raw product that Beef Products renders -- sold at an average of $.95 a pound last week, compared with 80 percent lean ground beef chuck for $1.84 a pound and 93 percent lean ground beef for $2.50 a pound.

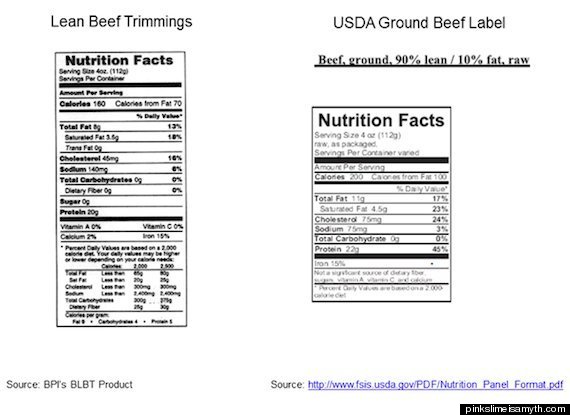

Beef Products maintains its product is a nutritiously equivalent or superior substitute for ground beef muscle, and a side-by-side comparison of nutrition labels for the two would yield the same conclusion.

But what the labels don't tell consumers, experts say, is the ultimate nutritional value behind the numbers on those labels. A 1996 Journal of Food Science report revealed that ground beef muscle is 69.2 percent soluble protein while lean finely textured beef is only 22.8 percent soluble protein -- the protein most easily digestible by children. (See a visual comparison in the graphic below.)

Additionally, ground beef muscle is about 18.3 percent collagen -- the predominant ingredient of connective tissue -- while lean finely textured beef is about 36.8 percent collagen. Collagen is what's considered an incomplete protein; its amino acid composition is different from that of a complete protein like muscle meat, eggs and fish. Complete proteins are used by the body for growth and repair, but people burn up the calories in incomplete proteins in about the way that they process sugar unless they are consumed with specific foods to result in a complete protein during digestion.

Treating the lean beef product with ammonia might also change the amino acids in proteins, further reducing the nutritional value, according to a 1980 University of California study.

But when it comes to consumer nutrition labels, complete and incomplete proteins are the same thing, making the two indistinguishable to those seeking information on what they're actually buying.

"They're calling this a meat; it's not. It's connective tissue and it is a much poorer quality protein even if they treat it, however they may treat it, to make it more digestible or more integrated," Sharon Akabas, associate director of Columbia University's Institute of Human Nutrition, told HuffPost.

Although the USDA's announcement might mark a step forward for "pink slime" critics, Siegel isn't ready to claim her victory, yet. She wrote on her blog Thursday morning that she's "still digging" for answers to questions like "Is there an even larger cost differential for schools who must shoulder labor charge to convert bulk beef to patties if they opt not to purchase the LFBT patties?" or "Does this create an even higher bar for districts wanting to avoid pink slime?"

"It's economic disclosure; it's an economic fraud issue," Zernstein said. "It's really not so much food safety. Put as much ammonia in it as you want. I don't care. Kill it. It still ends up being low quality, but you at least need to label it so much percent lean finely textured beef ... so I can say, 'I'm broke; it's low quality, but I'll buy it because I'm hungry.' The USDA knows better. Their labeling people blew it."

Although the USDA's announcement might mark a step forward for "pink slime" critics, Siegel isn't ready to claim her victory, yet. She wrote on her blog Thursday morning that she's "still digging" for answers to questions like "Is there an even larger cost differential for schools who must shoulder labor charge to convert bulk beef to patties if they opt not to purchase the LFBT patties?" or "Does this create an even higher bar for districts wanting to avoid pink slime?"

"It's economic disclosure; it's an economic fraud issue," Zernstein said. "It's really not so much food safety. Put as much ammonia in it as you want. I don't care. Kill it. It still ends up being low quality, but you at least need to label it so much percent lean finely textured beef ... so I can say, 'I'm broke; it's low quality, but I'll buy it because I'm hungry.' The USDA knows better. Their labeling people blew it."